Hu Shih

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (March 2024) |

Hu Shih | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

胡適 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hu in 1960 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese Ambassador to the United States | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 29 October 1938 – 1 September 1942 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Wang Zhengting | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Wei Tao-ming | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellor of Peking University | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1946–1948 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| President of the Academia Sinica | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1957–1962 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Zhu Jiahua | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Wang Shijie | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 17 December 1891 Shanghai, Qing China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 24 February 1962 (aged 70) Taipei County, Taiwan, Republic of China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Occupation |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Known for | Chinese liberalism and language reform | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Philosophical schools | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Region | Chinese philosophy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Philosophical interests | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Influences | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Academic background | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Academic work | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Institutions | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main interests | Chinese language and literature, redology | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Writing career | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Language |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | Modern (20th century) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Genres | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Subject | Liberation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literary movement | New Culture and May Fourth | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years active | from 1912 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notable works | Preliminary Discussion of Literature Reform (1917) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

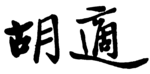

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 胡適 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 胡适 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hu Shih[1][2][3] (Chinese: 胡適; 17 December 1891 – 24 February 1962)[a] was a Chinese diplomat, essayist and fiction writer, literary scholar, philosopher, and politician. Hu contributed to Chinese liberalism and language reform and advocated for the use of written vernacular Chinese.[6] He participated in the May Fourth Movement and China's New Culture Movement. He was a president of Peking University.[7] He had a wide range of interests such as literature, philosophy, history, textual criticism, and pedagogy. He was also a redology scholar.

Hu was editor of the Free China Journal, which was shut down for criticizing Chiang Kai-shek. In 1919, he also criticized Li Dazhao. Hu advocated that the world adopt Western-style democracy. Moreover, Hu criticized Sun Yat-sen's claim that people are incapable of self-rule. Hu criticized the Nationalist government for betraying the ideal of Constitutionalism in The Outline of National Reconstruction.[8]

Hu wrote many essays attacking communism as a whole, including the political legitimacy of Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party. Specifically, Hu said that the autocratic dictatorship system of the CCP was "un-Chinese" and against history. In the 1950s, Mao and the Chinese Communist Party launched a campaign criticizing Hu Shih's thoughts.[9] After Mao's passing, the reputation of Hu recovered. He is now widely known for his high moral values and influential contribution to Chinese politics and academia.

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Hu was born on 17 December 1891, in Shanghai to Hu Chuan (胡傳), and his third wife Feng Shundi (馮順弟).[10] Hu Chuan was a tea merchant who became a public servant, serving in Manchuria, Hainan, and Taiwan. During their marriage, Feng Shun-di was younger than some of Hu Chuan's children.[10] After Hu Shih's birth, Hu Chuan moved to Taiwan to work in 1892, where his wife and Hu Shih joined him in 1893. Shortly before Hu Chuan's death in 1895, right after the outbreak of the First Sino-Japanese War, his wife Feng and the young Hu Shih left Taiwan for their ancestral home in Anhui.[11]

In January 1904, when Hu was 11 years old, his mother arranged his marriage to Chiang Tung-hsiu (江冬秀).[12] In the same year, Hu and an elder brother moved to Shanghai seeking a "modern" education.[13]

Academic career

[edit]Hu became a "national scholar" through funds appropriated from the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program.[12] On 16 August 1910, he was sent to study agriculture at Cornell University in the United States.[14] In 1912, he changed his major to philosophy and literature, and was elected to Phi Beta Kappa. He was also a member and later a president of the Cosmopolitan Club, an international student organization.[14] While at Cornell, Hu led a campaign to promote the newer, easier to learn Modern Written Chinese which helped spread literacy in China.[15] He also helped found Cornell's extensive library collections of East Asian books and materials.[15]

After receiving his undergraduate degree, he went to study philosophy at Teachers College, Columbia University, in New York City, where he was influenced by his professor, John Dewey and started literary experiments.[16] Hu became Dewey's translator and a lifelong advocate of pragmatic evolutionary change, helping Dewey in his 1919–1921 lectures series in China. Hu returned to lecture in Peking University. During his tenure there, he received support from Chen Duxiu, editor of the influential journal New Youth, quickly gaining much attention and influence. Hu soon became one of the leading and influential intellectuals during the May Fourth Movement and later the New Culture Movement.

He quit New Youth in the 1920s and published several political newspapers and journals with his friends. His most important contribution was the promotion of vernacular Chinese in literature to replace Classical Chinese, which was intended to make it easier for the ordinary person to read.[17] Hu Shih once said, "A dead language can never produce a living literature." [18] The significance of this for Chinese culture was great – as John Fairbank put it, "the tyranny of the classics had been broken."[19] Hu devoted a great deal of energy to rooting his linguistic reforms in China's traditional culture rather than relying on imports from the West. As his biographer Jerome Grieder put it, Hu's approach to China's "distinctive civilization" was "thoroughly critical but by no means contemptuous."[20] For instance, he studied Chinese classical novels, especially the 18th century novel Dream of the Red Chamber, as a way of establishing the vocabulary for a modern standardized language.[21] His Peking University colleague Wen Yuan-ning dubbed Hu a philosophe for his humanistic interests and expertise.[22]

Hu was among the New Culture Movement reformers who welcomed Margaret Sanger's 1922 visit to China.[23]: 24 He personally translated her speech delivered at Beijing National University which stressed the importance of birth control.[23]: 24 Periodicals The Ladies' Journal and The Women's Review published Hu's translation.[23]: 24

He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1932 and the American Philosophical Society in 1936.[24][25]

Public service

[edit]Hu was the Republic of China's ambassador to the United States between 1938[26] and 1942.[27][28] He was recalled in September 1942 and was replaced by Wei Tao-ming. Hu then served as chancellor of Peking University, at the time called National Peking University, between 1946 and 1948. In 1957, he became the third president of the Academia Sinica in Taipei, a post he retained until his death. He was also chief executive of the Free China Journal, which was eventually shut down for criticizing Chiang Kai-shek.

Death and legacy

[edit]

He died of a heart attack in Nankang, Taipei at the age of 70, and was entombed in Hu Shih Park, adjacent to the Academia Sinica campus. That December, Hu Shih Memorial Hall was established in his memory.[29] It is an affiliate of the Institute of Modern History at the Academia Sinica, and includes a museum, his residence, and the park. Hu Shih Memorial Hall offers audio tour guides in Chinese and English for visitors.

Hu Shih's work fell into disrepute in mainland China until a 1986 article, written by Ji Xianlin, "A Few Words for Hu Shih" (为胡适说几句话), acknowledged Hu Shih's mistakes. This article was sufficiently convincing to many scholars that it led to a re-evaluation of the development of modern Chinese literature.[30] Selection 15 of the Putonghua Proficiency Test is a story about Hu Shih debating the merits of written vernacular Chinese over Literary Chinese.[31]

Hu also claimed that India conquered China culturally for 2000 years via religion. At the same time, Hu criticized Indian religions for holding China back scientifically.[32]

Feng Youlan criticized Hu for adopting a pragmatist framework and ignoring all the schools of Chinese philosophy before the Warring States period. Instead of simply laying out the history of Chinese philosophy, Feng claims that Hu made the reader feel as if "the whole Chinese civilization is entirely on the wrong track."[33][34]

As "one of Cornell University’s most notable Chinese alumni,"[15] Hu has several honors there, including the Hu Shih Professorship and Hu Shih Distinguished lecture.[15] Hu Shih Hall, a 103,835-square-foot (9,646.6 m2) residence hall, was dedicated at Cornell in 2022.[35][15]

Philosophical contributions

[edit]Pragmatism

[edit]During his time at Columbia, Hu became a supporter of the school of Pragmatism. Hu translated "Pragmatism" as 實驗主義 (shíyànzhǔyì; 'experimental-ism').[b] Hu's taking to the thinking reflected his own philosophical appeals. Before he encountered Dewey's works, he wrote in his diary that he was in a search of "practical philosophy" for the survival of the Chinese people, rather than deep and obscure systems. He was interested in 'methodologies' (術).[36] Hu viewed Pragmatism as a scientific methodology for the study of philosophy. He appreciated the universality of such a scientific approach because he believed that such a methodology transcends the boundary of culture and therefore can be applied anywhere, including China during his time. Hu Shih was not so interested in the content of Dewey's philosophy, caring rather about the method, the attitude, and the scientific spirit.[37]

Hu saw all ideologies and abstract theories only as hypotheses waiting to be tested. The content of ideologies, Hu believed, was shaped by the background, political environment, and even the personality of the theorist. Thus these theories were confined within their temporality. Hu felt that only the attitude and spirit of an ideology could be universally applied. Therefore, Hu criticized any dogmatic application of ideologies. After Hu took over as the chief editor at Weekly Commentary (每周評論) in 1919, he criticized Li Dazhao and engaged in a heated debate regarding ideology and problem (問題與主義論戰). Hu writes in "A Third Discussion of Problems and Isms" (三問題與主義):

"Every isms and every theory should be studied, but they can only be viewed as hypothesis, not dogmatic credo; they can only be viewed as a source of reference, not as rules of religion; they can only be viewed as inspiring tools, not as absolute truth that halts any further critical thinkings. Only in this way can people cultivate creative intelligence, become able to solve specific problems, and emancipate from the superstition of abstract words."[38]

Throughout the literary works and other scholarships of Hu Shih, the presence of Pragmatism as a method is prevalent. Hu Shih avoided using an ill-defined scientific method. He described his own as experiential, inductive, verification-oriented, and evolutionary.[39]

Hu quotes Dewey's division of thought into five steps.

- a felt difficulty

- its location and definition

- suggestion of possible solution

- development of the suggestions

- further observation and experiment leads to acceptance or rejection.[39]

Hu saw his life work as a consistent project of practising the scientific spirit of Pragmatism as a lifestyle.

Skepticism

[edit]For Hu Shih, skepticism and pragmatism are inseparable. In his essay "Introducing My Thoughts" (介紹我自己的思想), he states that Thomas H. Huxley is the one person who most heavily influenced his thoughts.[40] Huxley's agnosticism is the negative precondition to the practical, active problem-solving of Dewey's pragmatism. Huxley's "genetic method" in Hu's writing becomes a "historical attitude," an attitude that ensures one's intellectual independence which also leads to individual emancipation and political freedom.

Chinese intellectual history

[edit]

Hu Shih brought the scientific method and the spirit of Skepticism into traditional Chinese textual study (kaozheng), laying the groundwork for contemporary studies of Chinese intellectual history.

In 1919, Hu Shih published the first volume of An Outline History of Chinese Philosophy. The later portion was never finished. Cai Yuanpei, president of Peking University where Hu was teaching at the time, wrote the preface for Outline and pointed out four key features of Hu's work:

- Method of proving for dates, validity, and perspectives of methodology

- "Cutting off the many schools" (截斷衆流), meaning ignoring all schools before the time of Warring States period and starting with Laozi and Confucius

- Equal treatment for Confucianism, Mohism, Mencius, and Xunzi

- Systematic studies with chronological orders and juxtaposition that present the evolution of theories

Hu's organization of classical Chinese philosophy imitated Western philosophical history, but the influence of textual study since the time of the Qing dynasty is still present. Especially for the second point, "cutting off the many schools" is a result of the continuous effort of Qing scholarship around ancient textual studies. Since the validity of the ancient texts is questionable and the content of them obscure, Hu decided to leave them out. In fact, before the publication of Outline, Hu was appointed to be the lecturer of History of Classical Chinese Philosophy. His decision of leaving out pre-Warring States philosophy almost caused a riot among students.[41][clarification needed]

In Outline, other philosophical schools of the Warring States were first treated as equal. Hu did not hold Confucianism as the paradigm while treating other schools as heresy. Rather, Hu saw philosophical values within other schools, even those considered to be anti-Confucian, like Mohism. Yu Yingshi commented how this paradigm followed Thomas Kuhn's Enlightenment theory.[42]

Feng Youlan, the author of A History of Chinese Philosophy, criticizes Hu for adopting a pragmatist framework in Outline. Instead of simply laying out the history of Chinese philosophy, Feng claims that Hu criticizes these schools from a pragmatist perspective which makes the reader feel as if "the whole Chinese civilization is entirely on the wrong track."[33] Feng also disagrees with Hu's extensive effort on researching the validity of the resource text. Feng believes that as long as the work itself is philosophically valuable, its validity is not as significant.[34]

Political views

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Liberalism in China |

|---|

| New Culture Movement |

|---|

|

|

Individualism, liberalism, and democracy

[edit]Unlike many of his contemporaries who later joined the Socialist camp, liberalism and democracy had been Hu's political beliefs throughout his life. He firmly believed that the world as a whole was heading toward democracy, despite the changing political landscape.[8][43] Hu defines democracy as a lifestyle in which everyone's value is recognized, and everyone has the freedom to develop a lifestyle of individualism.[44] For Hu, individual achievement does not contradict societal good. In fact, individual achievement contributes to overall social progress, a view that differs from the so-called "selfish individualism."[45] In his essay, "Immortality – My Religion," Hu stresses that although individuals eventually perish physically, one's soul and the effect one has on society are immortal.[46] Therefore, Hu's individualism is a lifestyle in which people are independent and yet social.[47]

Hu sees individual contributions as crucial and beneficial to the system of democracy. In "A Second Discussion on Nation-Building and Autocracy" (再談建國與專治), Hu comments that an autocratic system needs professionals to manage it while democracy relies on the wisdom of the people. When different people's lived experiences come together, no elite politician is needed for coordination, and therefore democracy is, in fact, easy to practice with people who lack political experience. He calls democracy "naive politics" (幼稚政治), a political system that can help cultivate those who participate in it.[48]

Hu also equates democracy with freedom, a freedom that is made possible by tolerance. In a democratic system, people should be free from any political persecution as well as any public pressure. In his 1959 essay "Tolerance and Freedom," Hu Shih stressed the importance of tolerance and claimed that "tolerance is the basis of freedom." In a democratic society, the existence of opposition must be tolerated. Minority rights are respected and protected. People must not destroy or silence the opposition.[49]

The Chinese root of democracy

[edit]A large portion of Hu Shih's scholarship in his later years is dedicated to finding a Chinese root for democracy and liberalism. Many of his writings, including “Historic Tradition for a Democratic China,"[clarification needed] "The Right to Doubt in Ancient Chinese Thought," "Authority and Freedom in the Ancient Asian World" make a similar claim that the democratic spirit is always present within the Chinese tradition.[50] He claimed that Chinese tradition included:

- A democratized social structure with an equal inheritance system among sons and the right to rebel under oppressive regimes.

- Widespread accessibility of political participation through civil service exams.

- Intragovernmental criticism and censorial control formalized by governmental institutions and the Confucian tradition of political criticism.

Constitutionalism and human rights movement

[edit]In 1928, Hu along with Wen Yiduo, Chen Yuan, Liang Shih-chiu, and Xu Zhimo founded the monthly journal Crescent Moon, named after Tagore's prose verse. In March 1929, he learned from Shanghai Special Representatives of National Party Chen De.

Hu criticized and rejected Sun Yat-sen's claim that people are incapable of self-rule and considered democracy itself a form of political education. The legitimacy and the competency of people participating in the political process comes from their lived experience. Sun's government also proposed to punish any "anti-revolutionary" without due process.

Hu wrote an article in Crescent Moon titled "Human Rights and Law" (人權與約法). In the article, Hu called for the establishment of a written constitution that protects the rights of citizens, especially from the ruling government. The government must be held accountable to the constitution. Later in "When Can We Have Constitution – A Question for The Outline of National Reconstruction" (我們什麼時候才可有憲法?—對於《建國大綱》的疑問), Hu criticized the Nationalist government for betraying the ideal of Constitutionalism in The Outline of National Reconstruction.

Criticism of the Chinese Communist Party after 1949

[edit]

In the early 1950s, the Chinese Communist Party launched a years-long campaign criticizing Hu's thoughts. In response, Hu published many essays in English attacking the political legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party.[9]

In the writing field, Lu Xun and Hu represented two different political parties. The political differences between the Nationalist Party and the Chinese Communist Party led to significantly different evaluations of the two writers. As a supporter of the Communist Party, Lu Xun was hailed by its leader Mao Zedong as "the greatest and most courageous fighter of the new cultural army." By contrast, Hu Shih was criticized by Communist-leaning historians as "the earliest, the most persistent and most uncompromising enemy of Chinese Marxism and socialist thought." The different evaluations of the two different writers show the complexity between two different political parties in modern China.[51]

Hu's opposition to the Chinese Communist Party was an ideological conflict. As a supporter of Pragmatism, Hu believed that social changes could only happen incrementally. Revolution or any ideologies that claim to solve social problems once and for all are not possible. Such a perspective was present in his early writing, as in the problem versus isms debate. He quotes John Dewey: "progress is not a wholesale matter, but a retail job, to be contracted for and executed in section."

Hu also opposed communism because of his ideological belief in individualism. Hu affirms the individual's right as independent from the collective. The individual has the right to develop freely and diversely without political suppression in the name of uniformity. He writes in "The Conflict of Ideologies":

"The desire for uniformity leads to suppression of individual initiative, to the dwarfing of personality and creative effort, to intolerance, oppression, and slavery, and, worst of all, to intellectual dishonesty and moral hypocrisy."[52]

In contrast to a Marxist vision of history, Hu's conception of history is pluralistic and particular. In his talk with American economist Charles A. Beard, recorded in his diary, Hu believed the making of history is only coincidental. Since he is a proponent of reformism, pluralism, individualism, and skepticism, Hu's philosophy is irreconcilable with Communist ideology. Hu's later scholarship around the Chinese root of liberalism and democracy is consistent with his anti-CCP writings. In a later manuscript titled "Communism, Democracy, and Cultural Pattern," Hu constructs three arguments from Chinese intellectual history, especially from Confucian and Taoist traditions, to combat the authoritative rule of the Chinese Communist Party:

- An almost anarchistic aversion of all governmental interference.

- A long tradition of love for freedom and fighting for freedom – especially for intellectual freedom and religious freedom, but also for the freedom of political criticism.

- A traditional exaltation of the individual's right to doubt and question things – even the most sacred things.[53]

Therefore, Hu regards the dictatorship of the Chinese Communist Party as not only "unhistorical", but also "un-Chinese".

Global policy

[edit]Along with Albert Einstein, Hu was one of the sponsors of the Peoples' World Convention (PWC), also known as Peoples' World Constituent Assembly (PWCA), which took place from 1950 to 1951 at Palais Electoral in Geneva, Switzerland.[54][55]

Writings

[edit]Essays

[edit]Hu Shih's works are listed chronologically at the Hu Shih Memorial Hall website.[56] His early essays include:

- A Republic for China (in The Cornell Era Vol. 44 No. 4) (PDF). Ithaca: Cornell University. 1912. pp. 240–242.

- The International Student Movement. Boston. 1913. pp. 37–39.

- 胡適文存 [Collected Essays of Hu Shih] (in Chinese). 1921.

Hu was an advocate for the literary revolution of the era, a movement which aimed to replace scholarly classical Chinese in writing with the vernacular spoken language, and to cultivate and stimulate new forms of literature. In an article originally published in New Youth in January 1917 titled "A Preliminary Discussion of Literature Reform",[57] Hu originally emphasized eight guidelines that all Chinese writers should take to heart in writing:

- Write with substance. By this, Hu meant that literature should contain real feeling and human thought. This was intended to be a contrast to the recent poetry with rhymes and phrases that Hu saw as being empty.

- Do not imitate the ancients. Literature should not be written in the styles of long ago, but rather in the modern style of the present era.

- Respect grammar. Hu did not elaborate at length on this point, merely stating that some recent forms of poetry had neglected proper grammar.

- Reject melancholy. Recent young authors often chose grave pen names, and wrote on such topics as death. Hu rejected this way of thinking as being unproductive in solving modern problems.

- Eliminate old clichés. The Chinese language has always had numerous chengyu used to describe events. Hu implored writers to use their own words in descriptions, and deplored those who did not.

- Do not use allusions. By this, Hu was referring to the practice of comparing present events with historical events even when there is no meaningful analogy.

- Do not use couplets or parallelism. Though these forms had been pursued by earlier writers, Hu believed that modern writers first needed to learn the basics of substance and quality, before returning to these matters of subtlety and delicacy.

- Do not avoid popular expressions or popular forms of characters. This rule, perhaps the most well-known, ties in directly with Hu's belief that modern literature should be written in the vernacular, rather than in Classical Chinese. He believed that this practice had historical precedents, and led to greater understanding of important texts.

In April 1918, Hu published a second article in New Youth, this one titled "Constructive Literary Revolution – A Literature of National Speech". In it, he simplified the original eight points into just four:

- Speak only when you have something to say. This is analogous to the first point above.

- Speak what you want to say and say it in the way you want to say it. This combines points two through six above.

- Speak what is your own and not that of someone else. This is a rewording of point seven.

- Speak in the language of the time in which you live. This refers again to the replacement of Classical Chinese with the vernacular language.

In the July 15 New Youth issue, Hu published an essay entitled, Chastity (贞操问题). In the traditional Chinese context, this refers not only to virginity before marriage, but specifically to women remaining chaste before they marry and after their husband's death (守贞). He wrote that this is an unequal and illogical view of life, that there is no natural or moral law upholding such a practice, that chastity is a mutual value for both men and women, and that he vigorously opposes any legislation favoring traditional practices on chastity. There was a movement to introduce traditional Confucian value systems into law at the time.

His 1947 essay We Must Choose Our Own Direction (我们必须选择我们的方向) was devoted to liberalism. He held the Jiaxu manuscript (甲戌本; Jiǎxū běn) for many years until his death.

Academic works

[edit]Among academic works of Hu Shih are:

- An Outline History of Chinese Philosophy. Vol. 1 (1919).

- The Chinese Renaissance: The Haskell Lectures, 1933. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1934).

- Hu Shih's Recent Writings on Scholarship (胡適論學近著). (Shanghai: Commercial Press, 1935). Including essay "Introducing My Thoughts" (介紹我自己的思想).

- "The Conflicts of Ideologies" in The Annuals of American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 28, November 1941.

Autobiography

[edit]The 184-page Autobiography at Forty (四十自述) is the only autobiography written by Hu Shih himself.[58]

Fiction prose and poetry

[edit]In 1920, Hu Shih published the collection of his poems Experiments (Changshi ji).[59]

The following excerpt is from a poem titled Dream and Poetry, written in vernacular Chinese by Hu. It illustrates how he applied those guidelines to his own work.

|

Chinese original |

|

|

都是平常情感。 |

It's all ordinary feelings, |

|

醉過才知酒濃。 |

Once intoxicated, one learns the strength of wine, |

His prose included works like The Life of Mr. Close Enough (差不多先生傳), a piece criticizing Chinese society which centers around the extremely common Chinese language phrase '差不多' (chàbuduō), which means something like "close enough" or "just about right":

As Mr. Chabuduo ("Close Enough") lay dying, he uttered in an uneven breath, "The living and the dead are cha.........cha........buduo (are just about the same), and as long as everything is cha.........cha........buduo, then things will be fine. Why...........be............too serious?" Following these final words, he took his last gasp of air.[62]

The Marriage (终身大事) was one of the first plays written in the new literature style. Published in the March 1919 issue (Volume 6 Number 3) of New Youth, this Hu Shih's one-act play highlights the problems of traditional marriages arranged by parents. The female protagonist eventually leaves her family to escape the marriage in the story.

Vernacular style

[edit]Hu Shih was part of the Chinese language reform movement and used the vernacular style in writing articles. The opposite style of writing is Classical Chinese, and one of the key leaders of this language was Zhang Shizhao. Hu Shih and Zhang Shizhao had only a ten-year age difference, but the men seemed to be of differing generations.[63]

In October 1919, after visiting Wu Luzhen in China, Hu Shih said with emotion: "In the last ten years, only deceased personalities like Song Jiaoren, Cai E, and Wu Luzhen have been able to maintain their great reputation. The true features of living personalities are soon detected. This is because the times change too quickly. If a living personality does not try his utmost, he falls behind and soon becomes 'against the time'''.[63] In Hu Shih's ideals, only dead people can hold their reputation; the world will soon know the real value and personality of a person if they do not follow the times. They will fall back in time soon if they are not trying to find changes that encourage writers in old China to follow the new revolution and start using the new vernacular style of writing. They cannot stay in the old style; otherwise, they will fall back in time. Furthermore, Hu Shih meant that China needed more new things.

Zhang was the biggest 'enemy' of the vernacular style, According to Liang Souming: "Lin Shu and Zhang Shizhao were two most significant people against vernacular style of writing in history".[63] But in fact, Hu Shih and Zhang Shizhao had a big age difference; when Zhang was at work in Shanghai, Hu was only a middle school student.

May Fourth Movement

[edit]Hu Shih participated in the May Fourth Movement, marking the beginning of modern China. Hu had a vision of the May Fourth Movement in China as part of a global shift in philosophy, led by Western countries. The global nature of the movement, in Hu's eyes, was particularly important, given China's relatively recent status as a global power. During the May Fourth Movement, Hu's political position shifted dramatically. As fellow thinkers and students of the movement looked towards socialism, Hu also gained a more favorable view of the collective, centralized organization of groups like the Soviet Union and the Third International. After the early 1930s, he changed back to his earlier positions, which put more weight on individualism. Hu then began criticizing communism such as Mao's government and the Soviet Union. During the chaotic period this movement developed, Hu felt pessimism and a sense of alienation.[64]

Towards the end of Hu's life, he expressed disappointment at the politicization of the May Fourth Movement, which he felt was counter to the primarily philosophical and linguistic issues that drove him to participate in it. No matter how Hu's position shifted through the course of the Movement, he always put the May Fourth Movement in a global, albeit Eurocentric, context.[65] Despite the implications of the May Fourth Movement, Hu Shih ultimately expressed regret that he was unable to play a larger role in his nation's history.[64]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "The Bureau at the Fair". Abmac Bulletin. 2 (7): 4. August 1940.

Dr. Hu Shih, Chinese Ambassador to the United States, Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia,{...}

- ^ "Department of State bulletin". 10 June 1944. p. 537.

The representative of the National University of Peking is Dr. Chen-sheng Yang, who has been acting dean of the College of Arts and Literature in the absence of Dr. Hu Shih.

- ^ "Introduction". Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

The Hu Shih Memorial Hall located on the Nankang campus was the residence where Dr. Hu Shih (1891–1962) lived from 1958 to 1962, during his tenure as the president of Academia Sinica.

- ^ H. G. W. Woodhead, ed. (1922). The China Year Book 1921-2. Tientsin Press, Ltd. p. 905.

Hu Shih, (Hu Suh). (胡適)–Anhui. Born Dec. 17, 1891.{...}

- ^ The Youth Movement In China. 1927. p. xii.

I am also indebted to many friends in China, especially to Dr. Hu Suh of the National University of Peking{...}

- ^ Ji'an, Bai (March 2006). "Hu Shi and Zhang Shizhao". Chinese Studies in History. 39 (3): 3–32. doi:10.2753/CSH0009-4633390301. ISSN 0009-4633. S2CID 159799416.

- ^ "Nomination Database – Literature". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ^ a b Chou, Chih-p'ing (2012). 光焰不熄:胡适思想与现代中国. Beijing: Jiuzhou Press. p. 288.

- ^ a b Zhou, Zhiping (2012). 光焰不熄:胡适思想与现代中国. Beijing: Jiuzhou Press. p. 202.

- ^ a b O'Neill, Mark (2022). China's Great Liberal of the 20th Century - Hu Shih: A Pioneer of Modern Chinese Language. 三聯書店(香港)有限公司,聯合電子出版有限公司代理. p. 18. ISBN 978-962-04-4918-5.

- ^ Grieder, Jerome (1970). Hu Shih and the Chinese Renaissance: Liberalism in the Chinese Revolution, 1917-1937. Harvard University Press. pp. 3–8.

- ^ a b Jolly, Margaretta (2001). Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms, Volume I A-K. London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. p. 442. ISBN 1-57958-232-X.

- ^ Mair, Victor H. (2013). Chinese Lives: The people who made a civilization. London: Thames & Hudson. p. 208. ISBN 9780500251928.

- ^ a b Chou, Chih-Ping; Lin, Carlos (2022). Power of Freedom: Hu Shih's Political Writings. University of Michigan Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-472-07526-3.

- ^ a b c d e Friedlander, Blaine (23 March 2021). "Residence hall names honor McClintock, Hu, Cayuga Nation". Cornell Chronicle. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ Egan 2017.

- ^ Luo, Jing (2004). Over a Cup of Tea: An Introduction to Chinese Life and Culture. University Press of America. ISBN 0761829377

- ^ Bary & Lufrano 2000, p. 362.

- ^ Fairbank, John King (1979) [1948]. The United States and China. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 232–3, 334.

- ^ Jerome B. Grieder, Hu Shih and the Chinese Renaissance Liberalism in the Chinese Revolution, 1917–1937 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1970), pp. 161–162. ACLS Humanities E-Book. URL: http://www.humanitiesebook.org/

- ^ "Vale: David Hawkes, Liu Ts'un-yan, Alaistair Morrison". China Heritage Quarterly of the Australian National University.

- ^ Wen Yuan-ning, and others. Imperfect Understanding: Intimate Portraits of Modern Chinese Celebrities. Edited by Christopher Rea (Amherst, MA: Cambria Press, 2018), pp. 41–44.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez, Sarah Mellors (2023). Reproductive realities in modern China : birth control and abortion, 1911-2021. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-009-02733-5. OCLC 1366057905.

- ^ "Shih Hu". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. 9 February 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ "PRESIDENT ASSURES CHINA'S NEW ENVOY; Tells Dr. Hu Shih We Will Keep Foreign Policy Based Upon Law and Order DIPLOMAT VOICES THANKS He Declares His People Will Fight On for Peace With Justice and Honor President Gives Assurance Will Fight On Indefinitely". The New York Times. 29 October 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ "Ambassador Hu Shih Recalled by China; Wei Tao Ming, Formerly at Vichy, Will Be His Successor". The New York Times. 2 September 1942. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Cheng & Lestz (1999), p. 373.

- ^ 成立經過. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

同年十二月十日,管理委員會舉行第一次會議,紀念館宣告正式成立,開始布置。

- ^ "Ji Xianlin: A Gentle Academic Giant", china.org, August 19, 2005

- ^ Putonghua Shuiping Ceshi Gangyao. 2004. Beijing. pp. 362–363. ISBN 7100039967

- ^ Deepak, B. R. (2020). India and China: Beyond the Binary of Friendship and Enmity. Springer Nature. p. 6. ISBN 978-9811595004.

- ^ a b Yu-lan Fung, "Philosophy in Contemporary China" paper presented in the Eighth International Philosophy Conference, Prague, 1934.

- ^ a b Chou, Chih-p'ing (2012). 光焰不熄:胡适思想与现代中国. Beijing: Jiuzhou Press. p. 36.

- ^ "Hu Shih Hall". Student & Campus Life | Cornell University. Retrieved 24 October 2022.

- ^ Hu 1948, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Hu Shih, 杜威先生與中國 (Mr. Dewey and China), dated July 11, 1921; 胡適文存 (Collected Essays of Hu Shih), ii, 533–537.

- ^ Hu Shih, 三論問題與主義 (A Third Discussion of Problems and Isms), 每週評論 no. 36, (Aug. 24, 1919); 胡適文存 (Collected Essays of Hu Shih), ii, 373.

- ^ a b Chang, Han-liang (2000). "Hu Shih and John Dewey: 'scientific method' in the May Fourth era – China 1919 and after". Comparative Criticism. 22: 91–103.

- ^ Hu, Shih (1935). 胡適論學近著 (Hu Shih's Recent Writings on Scholarship). Shanghai: Commercial Press. pp. 630–646.

- ^ Yu, Ying-shih (2014). Collected Writings of Yu Ying-shih. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press. p. 348-355.

- ^ Yu, Ying-shih (2014). Collected Writings of Yu Ying-shih. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press. p. 357.

- ^ Hu, Shih (1947), 我们必须选择我们的方向 (We Must Choose Our Own Direction).

- ^ Hu, Shih (1955), 四十年来中国文艺复兴运动留下的抗暴消毒力量—中国共产党清算胡适思想的历史意义.

- ^ Hu, Shih (1918). 易卜生主义 (Ibsenisim).

- ^ Hu, Shih (1919). Immortality – My Religion, New Youth 6.2.

- ^ Zhou, Zhiping (2012). 光焰不熄:胡适思想与现代中国. Beijing: Jiuzhou Press. p. 290.

- ^ "从一党到无党的政治 – 维基文库,自由的图书馆". zh.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- ^ Zhou, Zhiping (2012). 光焰不熄:胡适思想与现代中国. Beijing: Jiuzhou Press. pp. 290–292.

- ^ Shih, Hu (2013). Chou, Chih-P'ing (ed.). English Writings of Hu Shih. China Academic Library. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-31181-9. ISBN 978-3642311802.

- ^ Chou, Chih-p'ing (20 February 2020), "Two Versions of Modern Chinese History: a Reassessment of Hu Shi and Lu Xun", Remembering May Fourth, Brill: 75–94, doi:10.1163/9789004424883_005, ISBN 978-9004424883, S2CID 216388563, retrieved 17 December 2020

- ^ Hu, Shih (November 1941). "The Conflicts of Ideologies," in The Annuals of American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 28, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Hu Shih, "Communism, Democracy, and Cultural Pattern."

- ^ Einstein, Albert; Nathan, Otto; Norden, Heinz (1968). Einstein on peace. Internet Archive. New York, Schocken Books. pp. 539, 670, 676.

- ^ "[Carta] 1950 oct. 12, Genève, [Suiza] [a] Gabriela Mistral, Santiago, Chile [manuscrito] Gerry Kraus". BND: Archivo del Escritor. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Selected Bibliography of Hu Shih's Writings in English Language". Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- ^ 文學改良芻議

- ^ Hu 2016.

- ^ Haft 1989, pp. 136–138.

- ^ Haft 1989, p. 137.

- ^ "English translation by Kai-Yu Hsu". March 2010.

- ^ Hu Shih (1919). "Chabuduo Xiansheng 差不多先生傳" (PDF). USC US-China Institute (in Traditional Chinese and English). Translated by RS Bond. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Ji'an, Bai (2006). "Hu Shi and Zhang Shizhao". Chinese Studies in History. 39 (3): 3–32. doi:10.2753/csh0009-4633390301. ISSN 0009-4633. S2CID 159799416.

- ^ a b Chou, Min-chih (1984). Hu Shih and Intellectual Choice in Modern China. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. doi:10.3998/mpub.9690178. ISBN 978-0472750740.

- ^ Chiang, Yung-Chen (20 February 2020), "Hu Shi and the May Fourth Legacy", Remembering May Fourth, Brill: 113–136, doi:10.1163/9789004424883_007, ISBN 978-9004424883, S2CID 216387218, retrieved 17 December 2020

Sources

[edit]Secondary

[edit]- Bary, William Theodore de; Lufrano, Richard (2000) [1995]. Sources of Chinese Tradition: From 1600 through the Twentieth Century. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11271-8.

- Cheng, Pei-Kai; Lestz, Michael (1999). The Search for Modern China: A Documentary Collection. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0393973727.

- Chou, Min-chih (c. 1984). Hu Shih and intellectual choice in modern China. Michigan studies on China. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472100394.

- Egan, Susan Chan (2017). "Hu Shi and His Experiments". In Wang, David Der-wei (ed.). A New Literary History of Modern China. Cambridge, MA: Belknap. pp. 242–247. ISBN 978-0-674-97887-4.

- Grieder, Jerome B. (1970). Hu Shih and the Chinese renaissance: liberalism in the Chinese revolution, 1917–1937. Harvard East Asian series. Vol. 46. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674412508.

- Haft, Lloyd, ed. (1989). "Hu Shi, Changshi ji (Experiments), 1920". A Selective Guide to Chinese Literature, 1900–1949. Vol. 3: The Poem. Leiden: Brill. pp. 136–138. ISBN 90-04-08960-8.

- "Hu Shih". Living Philosophies. New York: Simon & Schuster. 1931.

- Li Ao (李敖) (1964). 胡適評傳. Literary Star Series (in Chinese). Vol. 50. Taipei: Wenxing shudian.

- Yang, Ch'eng-pin (c. 1986). The political thoughts of Dr. Hu Shih. Taipei: Bookman.

Primary

[edit]- Hu, Shih (c. 1934). The Chinese renaissance: the Haskell lectures, 1933. University of Chicago Press.

- ——— (1948). 胡适留学日记 [Hu Shih's Diary of Study Abroad] (in Chinese). The Commercial Press. Retrieved 16 March 2024 – via Taiwan eBook.

- ——— (2016) [1933]. 四十自述 [Autobiography at Forty]. Boya Bilingual Masterpieces Series (in Chinese and English). Translated by George Kao (乔志高). Beijing: Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press. ISBN 978-7-513574297. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020.

- ——— (1963) [1922]. The development of the logical method in ancient China. Paragon – via Internet Archive.

Further reading

[edit]- Chan, Wing-tsit. "Hu Shih and Chinese Philosophy." Philosophy East and West 6.1 (1956): 3–12. online

- Chinese Writers on Writing featuring Hu Shih. Ed. Arthur Sze. (Trinity University Press, 2010).

- "Dr. Hu Shih, a Philosophe", by Wen Yuan-ning. Imperfect Understanding: Intimate Portraits of Modern Chinese Celebrities. Edited by Christopher Rea. (Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2018), pp. 41–44.

- Life of Mr.pdf Another Mr. Chabuduo English Translation[permanent dead link] at University of Southern California

External links

[edit]- "The Chinese Renaissance": a series of lectures Hu Shih delivered at the University of Chicago in the summer of 1933. (see print Reference listed above)

- "Hu Shih Study" at newconcept.com (in Chinese)

- "Hu Shih in The Chinese Student Club At Teachers College"[permanent dead link] at pk.tc.Columbia.edu

- Hu Shih Memorial Hall Archived 28 May 2023 at the Wayback Machine in Nangang District, Taipei, Taiwan

- Hu Shi. A Portrait by Kong Kai Ming at Portrait Gallery of Chinese Writers (Hong Kong Baptist University Library).

- 1891 births

- 1962 deaths

- 20th-century Chinese writers

- 20th-century diarists

- Ambassadors of China to the United States

- Ambassadors of the Republic of China to the United States

- Boxer Indemnity Scholarship recipients

- Chinese Civil War refugees

- Chinese diarists

- Chinese essayists

- Scholars of Chinese literature

- Chinese scholars of Buddhism

- Cornell University alumni

- Educators from Shanghai

- Academic staff of Fu Jen Catholic University

- Language reformers

- Liberalism in China

- Members of Academia Sinica

- Members of the German Academy of Sciences at Berlin

- Members of the Prussian Academy of Sciences

- Ministers of science and technology of the Republic of China

- Modern Chinese poetry

- Academic staff of the National Southwestern Associated University

- Academic staff of Peking University

- Permanent Representatives of the Republic of China to the United Nations

- Philosophers from Shanghai

- Politicians of Taiwan

- Presidents of Peking University

- Redologists

- 20th-century Chinese philosophers

- Republic of China politicians from Shanghai

- Taiwanese educators

- Taiwanese people from Shanghai

- Teachers College, Columbia University alumni

- Writers from Shanghai

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- Scholars of ancient Chinese philosophy

- Chinese language reform