Jervis Bay Territory

Jervis Bay Territory | |

|---|---|

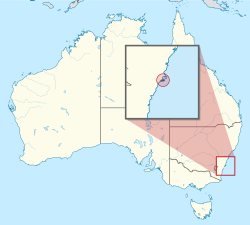

Location of the Jervis Bay Territory in Australia Coordinates: 35°8′55″S 150°42′49″E / 35.14861°S 150.71361°E | |

| Country | Australia |

| Separation from New South Wales | 1915 |

| Named for | John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent |

| Largest city | Jervis Bay Village |

| Demonym(s) | Territorian (locally) |

| Government | |

• Administered by | Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts |

| Parliament of Australia | |

• Senate | represented by Australian Capital Territory senators |

| included in the Division of Fenner | |

| Area | |

• Total | 67.8 km2 (26.2 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 307[1] |

• Density | 5.8/km2 (15.0/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+10:00 (AEST) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+11:00 (AEDT) |

| Postcode | NSW 2540 |

The Jervis Bay Territory (/ˈdʒɜːrvɪs, ˈdʒɑːr-/; "JBT")[2][3][4] is an internal Australian territory[5]. It was established in 1915 by the transfer of jurisdiction from the state of New South Wales to the federal Commonwealth of Australia,[6][7] in order to give the federal government control of a port in the vicinity of the landlocked Australian Capital Territory (ACT).[8]

History

[edit]Aboriginal Australian people. long lived over the area of Jervis Bay.[9] The area underwent significant change 18,000 to 7,500 years ago when the sea level rose, displacing inhabitants of previously coastal areas, resulting in dramatic population redistribution. The Yuin people have a continuing connection to the Jervis Bay area and in December 2016, applied for recognition of their native title.[10]

This article needs to be updated. (December 2024) |

Jervis Bay was sighted by Lieutenant James Cook aboard HMS Endeavour on 25 April, 1770 (two days after Saint George's Day) and he named the southern headland Cape St George.[11][12] In August 1791, the British convict transport ship Atlantic of the Third Fleet entered the bay and Lieutenant Richard Bowen named it in honour of Admiral John Jervis.[11][12] In November 1791, the Matilda, under Master Matthew Weatherhead, entered the bay to undertake repairs.[12] Survivors of the Sydney Cove shipwreck in 1797 reached the area by foot, heading to Port Jackson.[12][13] Explorer George Bass entered the bay on 10 December, 1797. He named Bowen Island. John Oxley, an English explorer and surveyor, travelled from Sydney by sea to explore the bay in 1819.[12]

Negotiations for the Federation of Australia reached three major agreements for proposed federal territories.

- First, a federal capital, a new, purpose-built city, should be located within the borders of New South Wales (NSW).

- Second, to help ensure such location did not give NSW too much influence on federal politics, that the new city and surrounds would be exclaved from NSW, as a separate federal territory.

- Third, that the federal government should have direct control and jurisdiction over at least one port.

The site of the capital city was not decided until 1908. All of the seriously considered sites were substantial distances inland. Therefore, the capital and the port would be separate. Ownership of Crown land in the Jervis Bay area was transferred from the NSW government to the federal government in 1909 (at the same time that ownership of the site of Canberra and the surrounding area was also relinquished by NSW).[14] In 1915, jurisdiction over the Jervis Bay Territory was transferred from the state of New South Wales to the federal Commonwealth of Australia.[15] To reduce the practical difficulties presented by the physical separation of the two territories, the government of NSW also agreed, in principle, that the federal government could build and take full control of a proposed rail corridor between Canberra and Jervis Bay,[citation needed] but this was never implemented.

The territory was administered by the federal government through its Department of the Interior, then its Department of the Capital Territory), Department of the Arts, Sport, the Environment, Tourism and Territories (1989-91), Department of the Arts, Sport, the Environment and Territories (1991-93), Department of the Environment, Sport and Territories (1993-96), Department of Transport and Regional Development (1996-98), Department of Transport and Regional Development (1998-2007), Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Local Government (2007-10), Department of Infrastructure and Transport (2010-13), Department of Infrastructure and Regional Development (2013-17), Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities (2017-2019), Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Cities and Regional Development (2019-20), Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications (2020-22) and then Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts (2022-).

Proposed nuclear reactor

[edit]

In 1969, Jervis Bay Territory was proposed as the site for a nuclear power plant but the proposal was cancelled in 1971. An access road had been constructed to the site, on the southeast corner of the bay near Murray's Beach and the site excavated and levelled. The levelled site is now the car park for Murrays Beach and its adjacent boat ramp.[16][17]

Geography

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2018) |

Having 67.8 km2 (26 sq mi) of land and 8.9 km2 (3 sq mi) marine reserve,[18] Jervis Bay Territory is the smallest of all the mainland states and territories of Australia. Jervis Bay is a natural harbour 16 km (10 mi) north to south and 10 km (6 mi) east to west, opening to the east onto the Pacific Ocean. The bay is situated on the southern coast of New South Wales about 198 km (123 mi) south of Sydney. The nearest major town is Nowra, about 40 km (25 mi) north, on the Shoalhaven River.

The majority of Jervis Bay embayment is part of Jervis Bay Marine Park (NSW State) while the waters within Jervis Bay Territory are part of Booderee National Park, formerly Jervis Bay National Park, (Commonwealth). Booderee means 'bay of plenty' or 'plenty of fish' in the local Aboriginal language.[9] The park itself encompasses approximately 90% of the territory of Jervis Bay and covers the overlap between Australia's northern and southern climatic zones. There are three small lakes within the territory: Lake Windermere, the largest, with an area of 31 ha (77 acres); Lake Mckenzie, 7 ha (17 acres); as well as Blacks Waterhole measuring 1.4 ha (3.5 acres). Ancient sand dunes overlay the sedimentary bedrock formations formed from upheaval of the surrounding marine environment 280–225 million years ago. Bowen Island, at the entrance to the bay 230 m (750 ft) north of Governors Head, is 51 ha (130 acres) in area. It has rookeries for the little penguin Eudyptula minor.

A wide variety of flora and fauna are native to the territory, with approximately 206 species of birds, 27 species of mammals, 15 species of amphibians, 23 species of reptiles and 180 species of fish native to the area.[19]

Demographics and settlements

[edit]

At the 2021 census, 310 people lived in the territory, the majority working and living at the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) base, HMAS Creswell.[20] Vincentia in NSW is the nearest town, roughly 3 km (2 mi) north of the border. All of Jervis Bay is covered within the postcode 2540.

The Wreck Bay Aboriginal Community Council owns approximately 68 km2 (26 sq mi), about 90% of the territory and exercises certain governance and representation functions for its community under the Aboriginal Land Grant (Jervis Bay Territory) Act 1986[21] The rest is managed by the Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities.

There are two villages in the Jervis Bay Territory:

- Jervis Bay Village (population 128)[22]

- Wreck Bay Village (population 152)[23] is an Aboriginal community.

HMAS Creswell

[edit]HMAS Creswell is the Royal Australian Navy College and associated naval facilities. The adjacent Jervis Bay Airfield is operated by the RAN. [citation needed]

Christian's Minde

[edit]There are several private leasehold properties in the Jervis Bay Territory within but not part of Booderee National Park. A group of buildings on the eastern foreshore of Sussex Inlet, known as the Christian's Minde Settlement, comprises of six separate parcels of land, four of which are leaseholds. The historical, heritage-listed Christian's Minde (Block 14) was founded in the mid-1880s by the Ellmoos family from Denmark.[24][25] Christian's Minde was promoted as the first guesthouse on the NSW south coast between Port Hacking and Twofold Bay when it was established in the 1890s. Pamir (Block 12) is also part of Christian's Minde Settlement. Descendants of the Ellmoos family lived at Christian's Minde (Block 14), Ellmoos (Block 9) and Ardath (Block 11) for over 130 years, and continue to live at Kullindi (Block 10) today. Members of the extended family are buried in a cemetery, surrounded by dense bush, which is managed by the Wreck Bay Aboriginal Community Council.[26][27][28]

Other leaseholds in Jervis Bay Territory are the Railway, Tram and Bus Union (RTBU) Holiday Park (Block 37)[29] and The Cove (former Bay of Plenty Lodges) (Block 28).[30][31][32]

Administration

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

Jervis Bay Territory voters are represented in the Senate together with those of the ACT and it forms part of the Division of Fenner (also with the ACT) for House of Representatives purposes[33] but it is not part of the ACT.

For most purposes, the territory is governed by the laws of the Australian Capital Territory which, by the terms of the Jervis Bay Territory Acceptance Act 1915, apply to the Jervis Bay Territory.[34] Residents have access to the ACT and federal court systems.

Jervis Bay Territory is administered by the Commonwealth Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts. Its Jervis Bay Administration handles matters normally handled by state or local government. Australian Federal Police provide policing. The Commonwealth government contracts the ACT government to provide various services like courts, education and welfare, the Government of New South Wales for rural fire services and community health, Shoalhaven City Council for waste collection and library services, and commercial providers for electricity and water supplies.

Jervis Bay Territory does not have its own elected local council. Although they are subject to ACT law and some services are contracted by the Commonwealth government to nearby councils in New South Wales, Jervis Bay Territory residents do not vote in either ACT or New South Wales elections. Aboriginal persons who are registered members of the Wreck Bay Aboriginal Community Council have voting rights in the council's meetings and elect the council's executive.

Section 61 of the Defence Force Discipline Act (DFDA) makes all Australian defence force members and "Defence Civilians" subject to the criminal laws of the Jervis Bay Territory regardless of where the offence occurred. This is a legal mechanism that makes defence personnel subject to the Crimes Act 1914 (Cth), the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Cth) and offences against the criminal law of the ACT, as military law, even if the offence is committed elsewhere outside Australia.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Jervis Bay Territory About the profile areas". Informed Decisions. Retrieved 9 June 2024.

- ^ Macquarie Dictionary, Fourth Edition (2005). Melbourne, The Macquarie Library Pty Ltd. ISBN 1-876429-14-3

- ^ The ABC Standing Committee on Spoken English: A guide to the pronunciation of Australian place names. Angus & Robertson 1957. p. 61.

- ^ Long, Jessica (2 October 2013). "You say Jervis, I say Jarvis…".

- ^ Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth) s 2b

- ^ "Seat of Government Surrender Act (NSW) Act 9 of 1915". Museum of Australian Democracy. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

This Act provided for the transfer of 28 square miles of land at Jervis Bay to the Commonwealth, in addition to the areas surrendered under the Seat of Government Acceptance Act 1909 and the Seat of Government Surrender Act 1909.

- ^ Jervis Bay Territory Acceptance Act 1915 (Cth)

- ^ "Documenting A Democracy". Museum of Australian Democracy. Archived from the original on 28 April 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

A portion of land at Jervis Bay was included in the Federal Capital Territory to provide a seaport for Australia's only inland capital.

- ^ a b "Our Culture". Parks Australia. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Gorton, Stan (13 December 2016). "South Coast Native Title meeting at Narooma a big boost for Yuin people". South Coast Register. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ a b Place Names of Australia (Reed, 1973).

- ^ a b c d e Crabb, Peter (2007). Jervis Bay and St Georges Basin 1788–1939 : an emptied landscape. Lady Denman Heritage Complex. ISBN 978-0958644730.

- ^ "The Sydney Cove". Tasmania Parks and Wildlife Service. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ^ Seat of Government Acceptance Act 1909 (Cth)

- ^ Jervis Bay Territory Acceptance Act 1915 (Cth)

- ^ McLaren, Nick (12 August 2019). "Nuclear reactor and steelworks plan once considered for pristine beaches of Jervis Bay". ABC News. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Kitchen, Carl (31 August 2023). "Nuclear power for Australia: A potted history". Australian Energy Council. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "Jervis Bay Territory". Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts. Australian Government. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ Lindenmayer, David; MacGregor, Christopher; Dexter, Nick; Fortescue, Martin (2014). Booderee National Park. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9781486300426.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Jervis Bay". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Aboriginal Land Grant (Jervis Bay Territory) Act 1986 (Cth)

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Jervis Bay (L)". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Wreck Bay". 2021 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 9 September 2024.

- ^ "Christians Minde Settlement, Ellmoos Rd, Sussex Inlet, ACT, Australia". Australian Heritage Database. Department of Environment and Energy. Archived from the original on 8 September 2024. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ Glenday, James; Kennedy, Adam (21 May 2021). "A 'risky operation', a group of dead quolls and a plan for the future of Aussie predators". www.abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 8 September 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

Ironically, for a marsupial devastated by European colonisation, one small group did well near the isolated, historic Christian's Minde site — one of the first settlements on this stretch of NSW coast.

- ^ "The Ellmoos Story". Sussex Inlet Community. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ "Christians Minde". Christiansmindejervisbay. Christiansmindejervisbay.com. 17 July 2016. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Kullindi Homestead". Kullindi Homestead. Archived from the original on 8 September 2024. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ "RTBU Holiday Park – Jervis Bay!". rtbuexpress.com.su. 16 November 2017. Archived from the original on 8 September 2024. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ "Jervis Bay, Sussex Inlet, & Hyams Beach holiday accommodation". Bay of Plenty Lodges. 11 November 2010. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ "Government Tenancy Registers - Jervis Bay". archive.act.gov.au. 13 March 2014. Archived from the original on 8 September 2024. Retrieved 8 September 2024.

- ^ "Walking trails brochure - Booderee National Park" (PDF). Environment.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ "Profile of the electoral division of Fenner (ACT)". Australian Electoral Commission. 19 November 2019. Archived from the original on 8 September 2024. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

The Division of Fenner also includes the Jervis Bay Territory.

- ^ "Jervis Bay Territory Governance and Administration". Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts. Archived from the original on 9 September 2024. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

Although the Jervis Bay Territory is not part of the Australian Capital Territory, the laws of the ACT apply, in so far as they are applicable and, providing they are not inconsistent with an Ordinance, in the Territory by virtue of the Jervis Bay Acceptance Act 1915.

External links

[edit] Geographic data related to Jervis Bay Territory at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Jervis Bay Territory at OpenStreetMap- Jervis Bay Territory Governance and Administration

- Jervis Bay – VisitNSW.com